The Botanical Garden of Carl Linnaeus

I have just returned from a week in Stockholm where I attended an international conference on the “Future of Places.” While the topic is significantly broad to allow for multiple interpretations a primary objective of the conference is to develop a “people centered agenda” highlighting the creation, design and management of public space as a priority for consideration at the UN-Habitat conference in 2016.

One of the most pressing issues facing the urban environment today is an appreciation and understanding of the role the natural world plays in shaping the public realm. Curiously absent as a topic of conversation at the conference, this need is heightened by the demographic shift of rural populations to cities where access to quality public open space is highly constrained.

This leads me to my day with Linnaeus, Sweden’s most famous natural scientist.

Born in 1707, Carl Linnaeus’ affinity for the natural world began in early childhood. His father, a Lutheran minister was an avid gardener providing Linnaeus with a love and fascination of plants that would consume him for the rest of his life.

Like many great naturalists it is Linnaeus’ early affiliation with nature that informed his study of living systems, ultimately leading to the development of a new classification of the plant kingdom based upon sexual characteristics. Linnaeus’ method of naming plants and animals, the binary nomenclature, remains in use throughout the world.

The instinctive bonds between human beings and living systems is the underlying principle of Biophilia, a concept developed by E.O. Wilson, the distinguished American naturalist who shares with Linnaeus an intense interest in observing and understanding the natural world. Like Linnaeus, Wilson’s genius and acute powers of observation were nurtured during childhood. Today, Biophiliac design is informing a new “nature movement” that transcends traditional environmentalism to connect children and adults to the natural world informing the manner in which cities are designed as integrated ecosystems.

In Biophilia, published in 1984 Wilson writes, “to the degree that we come to understand other organisms, we will place a greater value on them, and on ourselves.” A visit to the botanic garden of Linnaeus, the living textbook used in his teaching and research, provided me with a perfect opportunity to consider the importance of the natural world in the development of place and more specifically how the design of botanic gardens might inform the discussion of UN-Habitat 2016.

The botanical garden of Linnaeus is located in Uppsala 45 miles north of Stockholm. It is here in 1741, at the age of 34, Linnaeus was appointed professor of medicine and botany at the University of Uppsala. In this role he assumed management of the university’s botanical garden, the oldest in Sweden, and the accompanying residence where he would live, write, lecture and raise his five children.

One of his first projects was to restore the neglected botanical garden designed in 1655 by Olof Rudbeck, senior and damaged by fire in 1702. Through neglect the number of species in the garden had declined from 1,870 to 300 and Linnaeus complained that the residence and garden alike resembled a messy owl’s nest.

According to Uppsala University the famous architect Carl Hårleman was commissioned to lay out the garden and greenhouse while Linnaeus filled them with plants in accordance with his scientific and teaching methodologies.

The image below depicts the garden in the mid-1740’s after changes instituted by Hårleman and Linnaeus. It is from the dissertation Hortus Upsaliensis’ 1745, from the Linnaeus Museum collections and can be found on the web page of the Swedish Linnaeus Society, www.linnaeus.se/eng/index.html

Two and a half acres in size, the garden was designed using Baroque principles with plants arranged scientifically, some by family and others by geographic region. Today the garden contains 1,300 plants most of which are species that Linnaeus chose, collected and planted himself. The plants are labeled for identification.

Below is the label that identifies Linnaeus’ favorite plant, the twinflower (Linnaea borealis) which was named by his close friend and teacher Jan Frederik Gronovious in his honor.

Linnaeus is credited with naming nearly 8,000 plants. He also provided names for many animals as well as the scientific designation for humans: Homo sapiens. He chose the names of his supporters as inspiration (including his mentor Olof Celsius of centigrade fame) often naming the most beautiful plants in their honor. Common weeds or unattractive plants were named for his detractors.

The garden is divided into two parterres of perennial and annual plantings (seen in the map below as areas 6 and 7). The parterres resemble an outdoor library with four sections containing rows of planting beds enclosed by low hedges.

The perennial parterre is planted according to the 24 classes in Linnaeus’ sexual system providing early seasonal color in April and May. The annual parterre (which also contains biennials) follows a design used by the botanical garden in 1864.

Three small sunken gardens (numbers 9, 10 and 11 on the map) replicate river, lake and marsh ecosystems.

The main garden walkway, which connects the Orangery to the entrance gate is lined with plants chosen for their vibrant hues and association with local heritage using species popular in 18th century Sweden.

The garden is entered through a gate located along Uppsala’s main street. A forecourt visually connects the Director’s Lodge, where Linnaeus lived from 1743-1778, with the information shop and cafe.

The Director’s Lodge, opened as a museum in 1937, contains many of Linnaeus’ personal belongings including textiles, household furnishings and his medicine chest. Portraits of Linnaeus and his family as well as botanical specimens and notes from his travels throughout Sweden are also on display.

The upper floor of the lodge was dedicated to Linnaeus’ scientific work. It is here that he stored his extensive natural history collection and conducted lectures.

The proximity of the Director’s Lodge to the garden allowed Linnaeus to closely study the plants and animals at every hour and within every season. At night, lamplight in hand, he observed the plants while they “slept” and later wrote a dissertation on the subject. A prolific writer Linnaeus is credited with more than 180 works including books on the flora of Lapland and Sweden.

Constructed between 1742 and 1743 the Orangery was designed (with an advanced heating system) by Carl Hårleman to house plants unable to tolerate Sweden’s harsh winter climate. The image below is by artist Anita Mattsson.

Today the Orangery contains meeting areas as well as a permanent exhibition about the garden.

On either side of the orangery, Linnaeus planted spring and autumn parterres (12 and 13 on the garden plan). The autumn parterre contains many North American species, including asters. In late June the autumn parterre is a mass of verdant green foliage.

Exotic, potted species, which must be kept indoors during the cooler months are placed in the forecourt space between the spring and autumn parterres during the summer season.

During Linnaeus’ tenure the garden was home to a menagerie including peacocks, parrots, cranes, monkeys, hedgehogs and guinea pigs that lived partly in the Orangery and partly in a house and yard specifically designed for them in the north of the garden.

Monkey huts mounted on poles remain in the garden and can be seen in the historic engraving depicting the garden in 1770 below.

Linnaeus was particularly fond of a tame raccoon named Sjupp that entertained visitors to the garden. A gift from King Adolf Fredrik he was imported from New Sweden, a colony on the Delaware river in North America.

Linnaeus had a deep interest in America and Sjupp served as an icon for the exhibition Come into a New World: Linnaeus & America held during the Linnaeus tercentenary at the American Swedish Historical Museum. Fond of eggs, almonds,raisins, sugared cakes, sugar and fruit Sjupp, is said to have surprised visitors to the garden in search of such treats.

Upon Sjupp’s untimely death in 1747, Linnaeus, ever the scientist, dissected the remains and published a description.

Following Linnaeus’ death in 1778 his son Carl briefly managed the garden. In 1787 King Gustaff donated Uppsala Royal Garden to the university and the functions of the botanic garden designed by Linnaeus were moved to this new, larger site. With little care the garden was transformed into a romantic park and the Orangery was converted into a student clubhouse with architectural modifications.

In 1917 the Swedish Linnaeus Society was founded with a mandate to restore Linnaeus’ garden and home to its 1745 condition using the detailed descriptions provided through Linnaeus’ extensive records. Today the Society provides tours and manages the museum while the garden is maintained by Uppsala University.

The garden, museum, exhibition and shop are open from May through September and you can find updated information on activities and events at: www.botan.uu.se.

Linnaeus is buried in Uppsala Cathedral. When he died his collections and books were sold to Sir J. E. Smith, the first president of the Linnean Society of London.

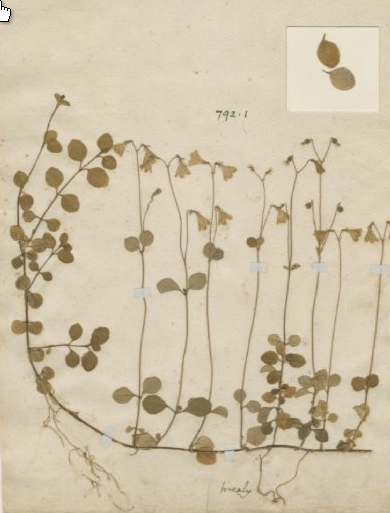

The Society also purchased Linnaeus’ manuscripts and correspondence and maintains an extensive website including 40,000 original specimens from Linnaeus’ collection that are digitized and available on-line. The specimen below, is Linnea borealis, Linnaeus’ favorite plant.

E.O. Wilson wrote, “nature holds the key to our aesthetic, intellectual, cognitive and even spiritual satisfaction.” As we ponder the future of cities I can think of no better way to end my visit with Linnaeus.

Copyright © 2013 Patrice Todisco — All Rights Reserved

Thank you for this excellent Landscape Note. I have enjoyed all of them, but I am particularly fond of this one. I taught two courses on E. O. Wilson at Beacon Hill Seminars, and I wish to thank you for the course that you taught at BHS. How we design our public places may be the key to a renewal of our aesthetic sense. Keep up the good work.

As the world becomes increasingly urbanized the value of well designed, managed and maintained public spaces (both natural and manmade) becomes critical to the quality of life of those living in cities. It’s one of the reasons that UN-Habitat is expanding its mandate to include public space in its ongoing work.

Love your posts, please keep them coming!

Andrea Langhahser

Thanks Andrea!

I do enjoy these posts as they teach me so much more about the history fo the gardens, gardeners and antrualists of the world… fascinating as always!

Donna,

I’m glad that you appreciate the pieces on Landscape Notes. I enjoy the process of researching the gardens/landscapes that I visit and sharing my insights with others. I’m always interested in feedback and ideas for future posts. Thanks!

I am as intrigued by Linnaeus as I am by your attendance at the international conference on “The Future of Places”. Although I would think it impossible to be a gardener and not at least know of Linneaus’ existence, your post has educated me more about the man and his particulars. I hope there is a blog post about “The Future of Places” conference coming soon.

Spending the day in Uppsala was the perfect antidote to the conference. Like you I knew about Linnaeus but was unaware of the scope of his work. As for the conference I’m working on a piece that integrates its content with my time in Stockholm. Thanks!

I look forward to reading the piece.

Pingback: Kaisaniemi Botanic Garden: Helsinki | Landscape Notes

Pingback: Chelsea Physic Garden | Landscape Notes